The collective had bold, if somewhat amorphous, plans to get back to the land. They would build a dwelling, plant a garden, make arts and crafts.

My dad, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford, had his own plans. We would spend a few months on the Land as research for a book about communal living. And so, in June of 1972, my folks packed up their Volvo station wagon and drove me and my twin brother Mike from our suburban Bay Area home, into the rugged coastal hills. We were 6 years old.

My memories of that summer are vivid fragments. I remember a cow stepping on my foot. I remember fresh milk from that cow being poured onto my bowl of corn flakes and the peculiar horror of encountering tiny chunks of cream. I remember the smell of body odor and incense. I remember inviting a man named Big John into my evening bath and the delight I felt when he lowered himself into the tub, fully clothed. A pack of naked kids ran around a creek howling; the song "American Pie" was always on the radio, with its mystifying lyrics about Chevys and levees.

Other memories were a little harder for me to parse. For instance, I remember taking my father's head into my lap and telling him that I was the doctor now and would cure him by pouring a thin stream of sand onto his forehead. As it turned out, my dad had dropped acid, something that happened a lot that summer on the Land.

I was also unaware, until years later, that my mother got up at dawn every morning and went to the henhouse to collect eggs, because she was concerned that Mike and I might not get enough protein otherwise.

All of which is to say: The grand vision of communal life on the Land crumbled pretty quickly. "There wasn't a large enough nucleus of people dedicated to the work of living communally," my dad explained to me recently. "Because that work was in conflict with the hippie ethic of doing your own thing. So it sort of came down to whoever got to the eggs first."

Where Were You in '72?

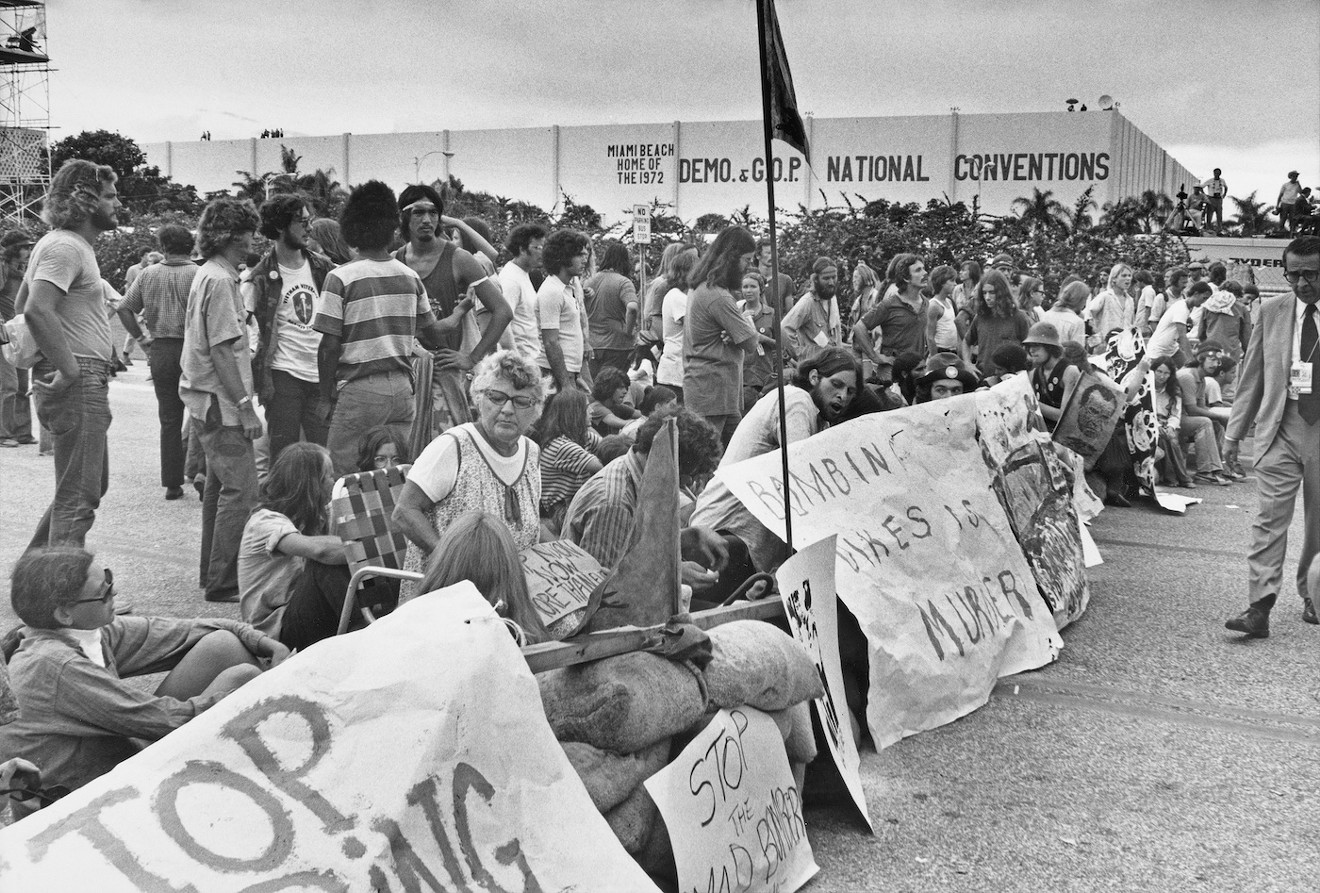

I thought a lot about that summer on the Land as I revisited the cover story I wrote 30 years ago for Miami New Times ("Where Were You in '72?" embedded at the bottom of this story). The piece detailed the dramas that unfolded around the Democratic and Republican national conventions in Miami Beach, the last time both were held in the same city.The short version is that antiwar activists were hoping to mount protests on a scale large enough to disrupt the GOP conclave, or at least overshadow the made-for-TV pageantry of Richard Nixon's re-nomination. In the end, more journalists showed up than actual protesters. Despite a few squabbles (quickly quelled by the liberal use of tear gas), the convention went off without a hitch. "The whole endeavor was half serious and half lark," the writer John Rothchild told me in 1992.

The central premise of my story was that the 1972 conventions served as the unofficial end of the Sixties, when the principled activism of that era gave way to a lassitude that would eventually corrode our political system and mire our citizenry in cynicism.

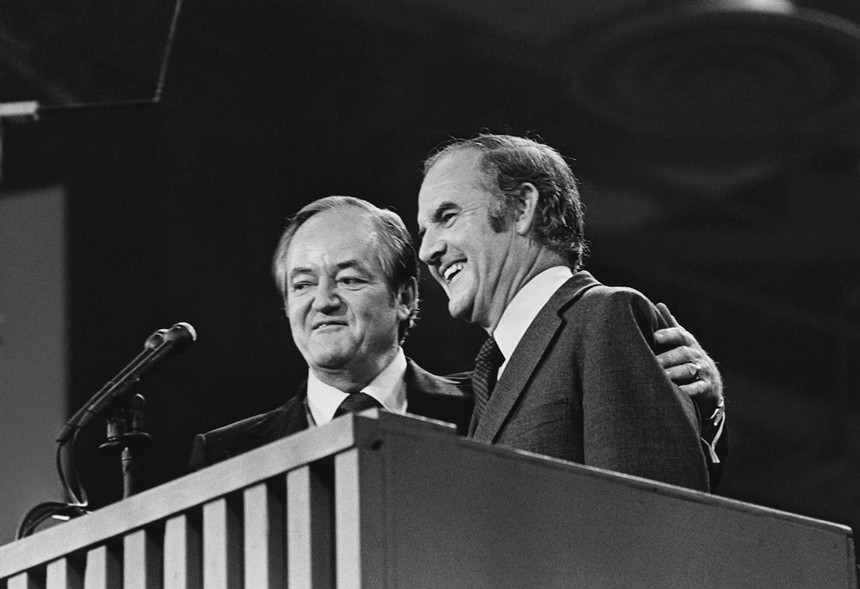

Hubert Humphrey and George McGovern at the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach

Photo by Archive Photo/Pictorial Parade Getty Images

Three decades on from that interview, it's hard for any citizen of good faith not to share in McGovern's sorrow.

Virtually every one of the legislative and moral achievements that marked the Sixties — from the civil rights movement to the Voting Rights Act, from the Great Society to the guarantee of reproductive rights — has been assaulted, if not reversed. The federal government, which once devoted its vast resources to waging a War on Poverty, would go on to launch a misguided War on Drugs, followed by an even more disastrous War on Terror.

The Watergate scandal that drove Nixon from office in 1974 produced a raft of reforms intended to curb abuses of power and crack down on the influence of corporations and lobbyists in political life. By 2016, nearly all had been overturned in court or allowed to lapse.

For all its sunny rhetoric about family values and limited government, the right wing's electoral strategy has become increasingly transparent. The GOP is a party devoted to stoking the primal grievances of its base, to transforming politics into an endless culture war, all while doing the bidding of corporate donors.

In this sense, Donald Trump was nothing more than the logical endpoint of conservatism, a nihilistic demagogue who treated the presidency not as a form of public service but as a source of personal power and profit.

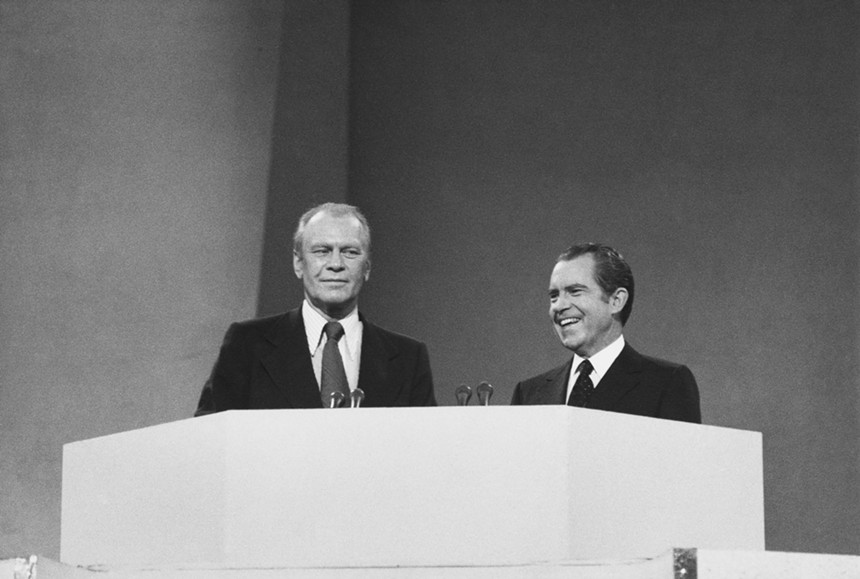

Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon at the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach

Photo by Archive Photo/Getty Images

Instead, the mainstream media treated him like a frontrunner, slavishly covering his rallies, amplifying his inflammatory rhetoric, pumping the oxygen of attention into his incoherent campaign.

The 2016 election, as you might remember, was marked by an echo of the Watergate break-in that ultimately led Nixon to resign. In this case, the burglars were Russian operatives who hacked into DNC email servers, looking for dirt that would help elect the Republican candidate.

This time around, though, America's journalists were oddly unconcerned with who had hired the burglars, or why. Instead, they eagerly publicized every scrap of damning material made available to them. The result was a potent smear campaign against the Democratic candidate, engineered by the Kremlin and carried out by our free press.

Glory Days

I will admit to an extreme personal bias in all this, as well as my own complicity. After all, I was a child of Watergate. I still remember watching Nixon resign from office, and I shared in the sense of vindication my parents felt. ("They finally got the bastard" were my mom's exact words.)I read All the President's Men repeatedly as a young man and went into journalism, driven by the notion that the first duty of the free press was to hold those in power accountable.

I also had the good fortune of joining the staff of Miami New Times during the ascent of the paper's influence. We had a murderer's row of reporters that included Jim DeFede, Kirk Semple, Kathy Glasgow, and Ben Greenman. Every week, we produced longform stories that sought to expose the corrupt underside of Miami's political, financial, and legal elite.

We were a rambunctious, quirky, and sometimes undisciplined operation. But we also spurred the Miami Herald and other local media to up their game.

Like most other staff writers, I eventually moved on, shipping off to grad school in the mid-'90s and switching my focus to writing fiction.

In the months before I left, I remember our former editor-in-chief, Jim Mullin, raving about this new technology, "the internet," and how it was going to change the journalistic and cultural landscape.

Mullin was absolutely right, and in ways that would ultimately contribute to the paper's decline. As more and more readers migrated online, they turned away from the in-depth investigative and exploratory journalism that drove New Times and other alternative papers. Why bother flipping the inky pages of a big, bulky tabloid when you could just pop online and "do your own research"?

Preserving Hope

I realize that I may be sounding my age at this point, voicing complaints about a world that no longer exists. I plead guilty to a certain embittered nostalgia. This was the basic tone of the piece I wrote back in 1992. The full story included a sidebar whose headline says it all: "Look Back in Anguish."Then again, it's impossible to read the accounts of those who took part in those conventions and not lament the state of America in 2022. These days, the most energetic precinct of the "counterculture" is inhabited by white supremacists hopped up on conspiracy theories and eager to subvert democracy. These are the folks ranting about "the system," attacking our Capitol, beating on police officers with flagpoles.

Their rage isn't focused on protesting an unconscionable war or attacking the greed that drives the excesses of capitalism. What they want is a "Christian Nationalist" state in which proto-fascist violence and intimidation shove aside free and fair elections.

That we have fallen so far away from the basic decency of our founding principles can only be viewed as an ongoing tragedy. To quote McGovern: That is really quite sad.

At the same time, I'm trying to preserve my own sense of hope.

One thing that helps is to step back from history and consider the role of the individual and, especially, the young citizens who might yet help us right the ship.

I'm thinking here of young Mitchell Kaplan, who was a long-haired 17-year-old back in August of 1972. Kaplan spent the last day of the GOP convention wandering around Miami Beach with his cousin, hoping to take part in a grand protest that never quite materialized. He had a number of adventures, at one point throwing a projectile at a cop ("it was the only violent thing I did") and getting sprayed in the eyes with mace for his trouble.

Looking back on the experience, Kaplan could see that "a lot of the agitation was really about getting attention, acting on a grand stage." But he still made the argument that "the period was one of compassion, where people were seeking some greater good. At least the rhetoric was good rhetoric."

Kaplan himself would go on to launch the beloved Books & Books bookstores in Coral Gables and around Miami and helped found the Miami Book Fair. He has become one of the most revered literary citizens in America.

It's possible, in other words, for good rhetoric to be matched by good deeds.

I think here, too, about my own daughter, Josie. At 15, she's already a member of our local town government, an organizer in the Sunshine Movement, a passionate activist who routinely gets me off my ass and off to local political rallies. And she wants to start an underground newspaper at her school.

What I often sense in Josie is a kind of fragile idealism. She has come of age in the era of political tumult, in which aggression and paranoia have infected the national bloodstream in ways more profound than any time in our history, aside from the Civil War. The results have been grim and pervasive: an attempted coup, a cycle of senseless gun violence, the outlawing of female bodily autonomy, and a suicidal negligence when it comes to climate change.

And yet Josie continues to deepen her political engagement. On better days, she believes that the demographic shift to a younger, more diverse electorate will usher in an era of progressive change in which it becomes possible, once again, to address the crises we face as a nation and species.

Her central academic interest is history. She understands, in a way that took me much longer to figure out, that only by looking back can we see the way forward.

Steve Almond was a staff writer at Miami New Times in the early 1990s. Now a novelist, essayist, and political commentator, he lives outside Boston with his family. All the Secrets of the World, his first novel, was published earlier this year by Zando Projects.