These six lives, of the roughly 5,651 who reside in the sleepy town of Surfside, continued that night while the lives of 98 of their neighbors had come to a swift, unexpected end. Many heard the roar of cascading concrete, which sounded like a slow succession of detonating bombs. No one knew then the extent of the tragedy that had just occurred, and those who were blocks away struggled to get information. Some checked social media. Others traded whispers with their neighbors.

As a cloud of debris descended over Surfside, so too did one of confusion. Naturally, residents asked questions: Who did I know in the building? What floor did they live on? What can I do to help?

The question those in Surfside are only beginning to broach is: “How can we move on?”

Especially now that the rest of the world has.

Lorin Jacobson, 1:25 a.m.

Lorin Jacobson is a father who has raised his kids in Surfside for more than 15 years. He likes to call himself the town’s unofficial mayor; he knows every family on his street and each police officer that patrols the area. He didn’t hear the thunderous clap caused by the crumbling 12-story building just half a mile from his house.His uncomfortable yet admittedly high-quality Samsung headphones had blocked out the sound. He did, however, pick up on a few faint sirens, which prompted him to remove his headphones. The high-pitched squeals of police car after police car crystallized in the salty night air.

On the rare occasions when Jacobson hears sirens in Surfside, he usually turns on his police scanner. But it was so early that Thursday morning, and false alarms are common. Besides, he thought, Nothing that bad ever happens here. So he strolled inside, locked the patio door, and went to bed.

“It sounds stupid, but I actually felt guilty that I didn’t run out,” Jacobson tells New Times. “I normally would have been the first person to the pile.”

Capt. John Healy was the first of the Surfside Police Department’s command staff to arrive on the scene.

Photo by Juan-Sebastian Martinez

John Healy, 1:25 a.m.

John Healy is the only employee of the Surfside Police Department who lives in Surfside. That’s usually not an issue, he says; the town has little to no crime. The most pressing matter the cops typically face is beachgoers who bring their dogs with them, a minor ordinance infraction.Minutes before the collapse on Thursday night, Healy got ready for bed. He laid out his clothes for the next day, a habit owed to ten years of active duty in the U.S. Air Force. That preparedness suddenly came in handy.

Five minutes after he tucked himself beneath his comforter, Healy got a call from Surfside Police acting sergeant Craig Lovellette. He threw on his uniform, raced out the door, and drove seven blocks in his unmarked Ford Explorer to where Champlain Towers South had once stood.

Healy was the first of the police department’s command staff to arrive on the scene. Through darkness and dust, he found officers Lovellette, Lage, and Ganbirazio all awaiting his instruction.

“I was in awe. I stood there looking for a few minutes at all of the debris still falling, the gray and silver from the dirt in the sky,” Healy recounts. “You hear people from the part of the building that didn’t collapse shining flashlights down, asking for help. Nothing of this magnitude has ever occurred in our small, little town.”

Hordes of people began arriving. They gawked or attempted to guide the search for their loved ones, inadvertently impeding the officials’ ability to save lives.

Healy called Tim Milian.

“I was in awe. I stood there looking for a few minutes at all of the debris still falling, the gray and silver from the dirt in the sky.”

tweet this

Tim Milian, 1:48 a.m.

It was Tim Milian and his parks and recreation staff who opened up the Surfside Community Center, a de facto town square, in the dark of night at 1:48 a.m. — about 30 minutes after the tower came down. Milian has worked at parks and rec for almost two decades. One of his favorite parts of the job is helping to organize Surfside’s summer camp program. He knows the camp puts smiles on the kids’ faces, and he takes pride in knowing he’s helping bring up the next generation of Surfsiders.He supported the decision to use the center as an evacuation and reunification site — one that stayed open 24 hours a day for 12 days, despite the fact that most of the staff works part-time and has at least one other job.

“We’re recreation people. We create programming for people to have fun,” Milian says. “This was more like crisis management. To my staff’s credit, everybody stepped up. People were here that work part-time and have two or three other jobs. This was their priority: To get here.”

After hearing about the collapse, Eliana Salzhauer headed to the community center.

Photo by Juan-Sebastian Martinez

Eliana Salzhauer, 1:30 a.m.

Surfside Commissioner Eliana Salzhauer hadn’t yet gone to bed and was still winding down from the day when she received a phone call from the town manager at 1:30 a.m. She thought when she heard him say there was a building collapse, it must have been something of a small scale, perhaps a balcony somewhere. It never occurred to her that it could be what she calls a “9/11 down the block.” Upon being given more details in a subsequent phone call with a town resident, she sat for a minute to process what was going on. Then she took a breath and headed to the community center.A former journalist with decades of experience covering traumatic events, she put her game face on.

Unlike Captain Healy in the direct line of fire, Salzhauer had a different role to play that night.

“I’m not going to run into a burning building or start pulling people out of the rubble — that’s not my training,” Salzhauer tells New Times. “But certainly I’m a community activist, so I can be at the community center making sure we’ve got people there. I can greet them right away with a hi. I can get their information. I can give them a T-shirt. I can get them fed. I can do all of that.”

“I thought I was sleepwalking. I thought it was a dream — this nightmare couldn’t happen.”

tweet this

Anthony Blate, 4 a.m.

At around 4 a.m, 72-year-old Anthony Blate was awoken by what he can only describe as a bad gut feeling. The retired pharmacist and stock trader is used to tossing and turning, but when he opened his eyes that dark Thursday morning, he knew he wouldn’t be able to shut them again so easily.Blate looked at his phone. As he stared at the screen, a text message popped up. A friend who lives on the south end of Surfside told him to get to 88th Street immediately. It was in that message that Blate learned Champlain Towers had collapsed.

He walked the half-mile to the site to find a war zone flooded with firemen and police officers. It didn’t feel real.

“In some ways, I thought I was sleepwalking,” Blate says. “I thought it was a dream — this nightmare couldn’t happen.”

Oliver Sanchez rode his bike five blocks to the scene at around 6:15 that morning.

Photo by Juan-Sebastian Martinez

Oliver Sanchez, 6 a.m.

Oliver Sanchez, 62, woke up to Nextdoor notifications on his phone. Nothing specific had been communicated to residents, many of whom were still fast asleep, away from the chaos. The collapse had clearly caught Surfside’s town officials off-guard, and residents like Sanchez felt literally and metaphorically left in the dark even as first responders and politicians were still grappling to understand the extent of the disaster.So, like Blate, Sanchez went to see it for himself. The artist’s instincts told him to ride his bike five blocks to the scene at around 6:15 that morning, inching right up to the debris.

“I didn’t need to rely on television and newspapers. It’s important to get that perspective because that’s what the whole world sees. But not when you live just blocks away,” Sanchez says. “I wanted to have my own personal understanding of what was going on, just as a guy in his bathing suit on his bike.”

He did the same when he traveled to New York in 2001 a month after the 9/11 attacks. He used to hold a job in the World Trade Center in the late 1970s and needed to see the site for himself.

Surfside’s collapse site appeared eerily familiar. Only this time it was in his backyard.

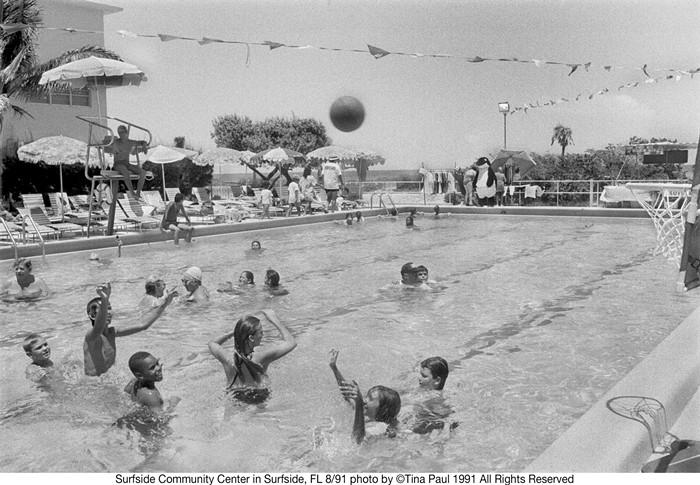

Since the 1960s, Tina Paul has preserved her memories of the town through her photography.

Photo by Tina Paul

A Tropical Postcard

Surfside looks like something out of a tropical postcard. Single-family homes and palm trees dot residential neighborhoods, neighbors greet each other with smiles, parents and their children walk or bike to nearby beaches on sunny afternoons.But the glamorous beachside paradise wasn’t always accessible to families and retirees the way it is today. In the 1930s, before Surfside was declared an official municipality, it was home to the Surf Club, an upscale two-story building created for the rich and famous visiting or living in Miami Beach. Back then it was a private oasis for the wealthy, hosting the likes of Elizabeth Taylor, Frank Sinatra, Sir Winston Churchill, and the Shah of Iran.

In the second half of the 1930s, the City of Miami Beach sought to annex an unincorporated slab of what is now Surfside. Resident historian of HistoryMiami Museum, Paul George, explains that Miami Beach had been riding the high of a financial upswing, and annexing the land was viewed as a way to increase revenue by attracting more tourists. But 35 residents of the then-unincorporated area who were members of the Surf Club didn’t want to jeopardize their beachside haven. So they banded together, signed a charter of incorporation, and officially established the Town of Surfside on May 18, 1935.

Development continued to boom throughout the second half of the 20th Century. Tina Paul, a professional photographer who serves as the town’s vice mayor, noticed an onslaught of not-so-subtle changes as she grew up in Surfside. Since the 1960s, she has preserved her memories of the town through her photography. A graduate of the School of Visual Arts New York City, Paul created a photo exhibit titled “Surfside: Transforming Tides,” to capture the things that made the town special before those features were lost to incoming commercial developments. Her exhibit hung on the walls of her beloved community center for four months in 2016.

“It was just a really beautiful, quiet, friendly neighborhood,” Paul recalls. “I always felt that my Miami Beach photos were really unusual to people. But it was normal life to me. It was like I went to document what was normal life to me growing up, something people in other places had never seen.”

When she visited Surfside as an adult, she didn’t really take note of the changes to the town. Upon completing her studies in New York, she moved back to Surfside for good in 2011 to take care of her parents. After the move, it was impossible not to pick up on the booming commercial zone and residential high-rises that popped up along Collins Avenue.

“You see your world upside down in a way,” Paul says. “Not the world I remembered.”

Other Surfsiders have been fighting for decades to maintain the town that Paul’s photography sought to preserve. Nearly 800 residents banded together in 2018 to kill a $33.5 million public-private partnership proposal that would have allowed an outside developer to build a town hall, a police department, a 431-space parking garage, a gym, office space, and more than 10,000 square feet of retail stores and restaurants. Residents like Paul think the proposal was too much for the small town — less than a single square mile in total area — to bear.

The true charm of Surfside, those residents say, has always been the family-oriented community and laid-back beach vibe. One of the town’s staple establishments, the Surfside Community Center, serves as a hub for residents of all ages. Paul vaguely recalls learning to swim in the center’s pool, taking dance classes, playing tennis, and watching adults come to use computer labs before it became the norm to own a desktop (or two) at home.

The center relocated to its bigger and brighter location on Collins Avenue in June 2011. Its revamped aquatic center, equipped with a swirly water slide, summer camp programs, and fitness classes, attracts children and 100-year-olds alike.

To residents, the community center is what unites the town. Anthony Blate, 72, often goes to chat with the local 90- and 100-year-olds after he swims in the center’s pool, which he prefers to the hustle and bustle of the public beach.

A resident of 28 years, Blate has watched as more and more people discovered what he feels is South Florida’s best-kept secret. His fear is Surfside growing beyond what it can sustain — of attracting not only the public eye but that of ravenous real estate developers. With its 12-story limit for high-rise buildings, the town has dodged the leer of developers before, but the risk always looms.

“Is getting as many people here the best thing for quality of life? I’m not so sure,” Blate says. “When you move somewhere special, why do you want it to change so much?”

Those in charge of making decisions about development and happenings around the city are fond of small-town drama.

Since the new commission was elected at the onset of the pandemic, it has been a hotbed of petty squabbles among representatives. One of the only times Surfside gained statewide media attention was when Eliana Salzhauer flipped Mayor Charles Burkett the bird after he made the case that evangelical Christians should be added to a resolution in support of Asian-Americans experiencing hate crimes.

Government disagreements are well-documented in the town’s monthly newsletter, the Surfside Gazette, where members of the commission often openly carp at one another. But regardless of whether they lean left or right, they see eye to eye in one crucial respect: their indomitable enthusiasm for life in their small town.

Tragedy Strikes

When the Champlain Towers South building caved in, it signified the tragic end to 98 lives. It also erased any semblance of safety for those who survived.No one thought a tragedy of this magnitude could ever occur in Surfside, where only three police officers tend to patrol at a time, owing to the town’s small size and the usual absence of emergencies. Even Captain Healy, who has served in the military for more than two decades, felt shell-shocked.

“I’ve seen plane crashes,” he says. “I’ve dealt with every critical incident you could ever imagine, but this is the largest critical incident I’ve ever had to deal with.”

Two days after the collapse, Miami-Dade County’s mayor, Daniella Levine Cava, directed the Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources to conduct 30-day audits of residential properties taller than five stories and older than 40 years of age. She urged municipalities to do the same, and the City of Miami soon followed through with the release of letters encouraging structural inspection of all buildings fitting the same criteria. Champlain Towers South had been due for its 40-year recertification, as required by Miami-Dade County. Fear spread across the state, the nation, and the world as news stations turned their focus to reporting on Surfside and other buildings that might be at risk. People everywhere wondered whether this could happen in their town, too.

For Surfside residents marooned amid the news crews, gawkers, and debris floating through their town, that fear had tangible consequences.

The remains of 98 people were recovered in the days and weeks that followed the collapse.

Photo by Michele Eve Sandberg

Jacobson, who runs the Surfside Boy Scout and Cub Scout troops, knows firsthand how traumatic the event has been on the town’s children. He says that through the Scouts programs, he’s helped raise most of the young boys in Surfside alongside his son.

“The kids are the ones who are suffering right now. Little by little, this one had a breakdown, that one had a breakdown, the other one had a breakdown,” he says. “They’re not talking about it much. And then all of a sudden they just have a breakdown.”

Then came the Fourth of July. In a year not blighted by chaos, Jacobson and his family would have trekked to the crowded beach, then returned home for a celebratory barbecue. This year, the only bodies on the beach were there to mourn the ones that were lost. Jacobson didn’t see his neighbors grilling outside their homes, he didn’t see the annual fireworks display, nor did he see the community come together in the same way it had in years past.

“The town was dead,” he says.

At 10 p.m. that night, the remains of the 12-story building were demolished. Jacobson stayed locked inside his home. Others snuck out.

Oliver Sanchez heard two kabooms, hopped on his bike, and, despite official warnings to stay indoors and away from the demolition area, rode to the site to see the finale for himself.

“I went over there and stayed away from the dust cloud. There was a creepy glow [around the site],” he says. “First we saw the [June 24] collapse from that surveillance camera. Then we saw the demolition.”

As the last of the building came down, firefighters continued their rescue mission, searching for any survivors that might still be trapped beneath the tons of rubble. That effort shifted to a recovery mission on July 8, once the inevitable became clear.

Between the loved ones of those who’d perished and the residents of the building who’d survived the collapse, healing looks different. And it’s ongoing.

Rabbi Aryeh Citron of the Shul in Surfside straddles both sides of the collapse — the living and the dead. He prayed with survivors at 6 a.m. in the Surfside Community Center on the day of the collapse. He also presided over funeral after funeral in the days and weeks that followed.

“Mostly, among the survivors, there’s happiness that they survived. But there’s also a lot of difficulty and pain,” Citron says. “They have to start their lives totally from scratch in terms of possessions and trying to find new housing.”

Citron knew five people who were lost in the wreckage. Blate lost his elementary-school physical education coach from 60 years ago, Arnold Notkin; Jacobson lost some of his Scouts; and all of Surfside lost a fair portion of its spirit as residents were left shaken by the fallout.

Rebuilding

The media were the eyes and ears for the world as the county held press conferences en masse. But heads began to turn elsewhere as worldwide events warranted, and attention gradually receded. It was as if the town had suddenly hit low tide after almost a month. As time passed, hopes of finding survivors diminished in tandem.Residents are reconciling with tragedy in their own ways. Now that the bodies of the missing 98 people have been recovered, it’s clear that deeper wounds remain, even for those who weren’t related to someone who was lost.

Two days after the disaster, the summer camp based out of the Surfside Community Center was up and running for a temporary stint at the Ruth K. Broad K-8 school seven minutes away from the community center and 16 minutes from the collapse site. The camp is now wrapping up its final few weeks back at the community center. Though the building is the same, none of the kids who returned to the camp are. Still, everyone wanted Surfside’s children to resuscitate whatever was left of a “normal” summer.

“People want a sense of normalcy, a routine,” Milian says over the muffled giggling of kids in the distance. “That’s what the community center provides. We’re on the road to recovery. I don’t think anybody will ever be 100 percent back to normal. It’s like that Pink Floyd song ‘Another Brick in the Wall’: It’s one brick at a time as we start to move forward.”

Eliana Salzhauer says the commission's number-one priority is to see some tangible change come out of the collapse. She’d like to see the 40-year recertification process whittled down to 30 years, and a requirement that buildings undergo geotechnical testing.

It’s also vital to have a proper memorial made out of the collapse site, Salzhauer says.

“It’s a graveyard,” she tells New Times. “I don’t need to talk to the families to know that it should be a memorial.”

Although commission members have mostly put aside their differences to deal with the tragedy, she’s skeptical that the cooperation will continue.

“The question is going to be what are we left with afterward,” Salzhauer says. “That’s where we’ll really see what people are made of and what their allegiances are.”

A member of the town’s planning and zoning board, Oliver Sanchez predicts developments old and new and near and far will be examined with a fine-tooth comb. Will the buildings fall tomorrow? Not likely, Sanchez predicts. But he wonders what resolution might come from the Champlain Towers collapse.

“They cut corners, then there’s a collapse,” he says. “There’s a memorial and the last thing is people go to jail. I wonder who will go to jail here. Probably nobody.”

Looking to the future, nothing is certain for the small town. Residents can only find certainty in the fact that Surfside will forever be marked by June 24 and the madness thereafter.

“Even when the spotlight is gone, we’ll still be here. Surfside is not a blank slate once the Champlain dust is settled,” Sanchez says. “It’ll never settle for the victims and their families. But there has to be some peace.”